Ex Corde

One month and a day after my son was born, I collapsed at work. My coworker and I had just unloaded a shipment of foam packaging materials we use to ship our products (nothing heavy, mind you) and put them all away, when I got a familiar fluttering where my ribcage meets my gut. This was accompanied by a lightheadedness and fading vision. This wasn't new; it happens almost every time I mow my lawn. I can usually just breathe through it. Not this time. I woke up flat on my back, my coworker kneeling next to me saying my name.

I don't remember what I said, but I'm sure it was eloquent and articulate. We slowly got me back on my feet, and I insisted that I could get back to work.

I felt like I had been in a deep sleep and rudely awakened. I was a bit wobbly and my back hurt from the fall. My coworker kept asking if I thought I should go home. After some consideration, I thought maybe I should go to the ER to make sure I didn't have a concussion from hitting the floor.

Getting behind the wheel of a car after losing consciousness felt dangerous and irresponsible, so I called my wife, who was at home on maternity leave with our newborn. She promptly came to get me with the baby in tow and whisked me off to the hospital. On the way we agreed that the ER wasn't the place we wanted our newborn to be hanging around, so she dropped me off and took him home. My mom agreed to come sit with me and drive me home once I was given the OK.

After checking in at the front desk, I was called into the triage room where a nurse velcroed a blood pressure cuff around my arm and placed a little plastic clamp on my index finger. I answered her questions about why I had come in, and she dutifully typed my responses into a computer. Then she apologized and said that she was required to ask some additional questions. Among them was “have you ever wanted to go to sleep and never wake up?”

I hate this question. I hate it because my honest answer, “almost every day of my life! That would be delightful!” would only buy me a week locked inside the Behavioral Sciences Unit. With a wife and newborn at home, I opted to answer “no.”

With the nuisance psychiatric questions out of the way, the nurse noted that my blood pressure and heart rate were a little higher than they ought to be.

We all know that hospital waiting rooms are the first level of the inferno; you can walk in with your severed arm in a Hefty bag full of ice and they'll have you take a seat and wait for an hour while you bleed all over the magazines. This is not the case when you're a bit tachycardic.

The next thing I knew, I was ushered into another little room where I was instructed to lie down and nurses placed square stickers on various parts of my body that were then connected to wires. It was an EKG. An EKG is one of those terms that gets thrown around on tv medical dramas, urgently shouted by sexy doctors with a patient dying in front of them on a stretcher. My nurses stood there calmly looking at a small monitor and discussed their weekend plans. I decided to put off worrying for the moment and relax. I’ve always been in good health, this was probably nothing.

I was taken to one of the ER exam rooms where I hardly had to wait more than a few minutes to be seen by the doctor, who was polite and thorough in his questions. My story and back pain were enough for him to order some x-rays to see if I cracked a vertebrae or rib, and a nurse arrived with a wheelchair to roll me down the hall. My mom arrived as I was saddling up, and sat down to wait for my return.

I enjoyed riding through the labyrinthine halls of the hospital with people passing by on foot. They looked at me suspiciously with my long hair and bushy beard and tried to hide the “hard living finally caught up with ya, huh?” look in their eyes. I grinned and waved.

We arrived at the x-ray room and the nurse who had pushed me there engaged the parking brake, helped me to my feet, and left. My back pain was getting worse and I was starting to get a headache. A woman in scrubs stepped out from a little room in the back of the dimly lit space; she was young, tall, and pretty. At least, I assume she was pretty. She - and about fifty percent of the hospital staff - had surgical masks on because of the uptick in Covid cases the area had been seeing. She could have been hideously ugly for all I know - like I said, it was dark - but there was a prettiness about her. But maybe that was just a trick my brain was playing on me to help calm my nerves.

I was positioned standing amongst several large mechanical arms, each equipped with boxes, handles, and lenses of varying size, told to put my arms up (whrrrclik), out (whrrrclik), down (whrrclik), and so on. I did this with some discomfort, and wondering how my family’s life would be affected if I had a fractured something or other. Then, in an awful and horrifying turn of events, the pretty woman in the booth stepped out and said:

“Okay, I need your shirt off for this next one.”

The horror. The shame! When I was a young man, I wouldn’t have given this a second thought, I might have even offered to take my pants off as well. Now, as a middle aged man who spends most of his work day on his butt, I have the physique of a potato with pencils for arms and legs.

“Do you need help?” asked the young lady, her eyes sympathetic above her mask.

“Nah, I’m good.” I said, wincing as I pulled my t-shirt over my head. I wondered if it was bright enough in there for her to see me blushing.

“Lie down here,” she said, gesturing to a table with a loose fitting sheet over it, “and take your pants down. You don’t have to take them all the way off. You can keep your underwear on.”

“Thank God for small mercies,” I thought to myself.

The young lady returned to her compartment and activated the contraption above me. Why does my dental hygienist cover me in a lead blanket to x-ray my teeth, but I can be half naked for this? One of life's many mysteries.

My wheelchair driver returned after I got my clothes back on, and I took my seat again. If I hadn’t still been a bit foggy or wishing I had the body of Brad Pitt in Thelma & Louise I might have said something witty like “Home, Geeves.” Oh well. It probably wouldn’t have gone over anyway.

Mom was still sitting in the corner of my room in the ER. She smiled at me as I was wheeled in but the worry in her eyes was hard to miss. The nurse engaged the parking brake and helped me from the wheelchair to the bed. “The doctor will come see you after he’s looked at your x-rays,” she said. “Do you need anything else? How’s your pain?”

“I’m fine,” I lied. My back was actually making me quite uncomfortable, but two Tylenol would cost me eighty dollars. With some often repeated stock well-wishes, the nurse took the wheelchair and left. I looked at my mother, whose smile was giving way to her concern and curiosity. “Hey, Mom.”

I told my mom the series of events that had brought me there - the fluttering, the dizziness, the waking up on the floor - and thanked her for being there instead of my wife and newborn. She agreed that they were better off at home. We chatted and theorized about why I had fainted; I shrugged it off as a result of being overtired from sleepless nights tending to the baby, but Mom was not convinced.

Nurses popped into the room from time to time to hook me up to tubes and wires and check my vitals. Each time beginning with “can you tell me your name and birthdate?” followed by the scanning of barcodes and entering of numbers into the wall-mounted computer. It seemed like a lot of steps just to check my pulse.

The doctor eventually arrived and said that the x-rays showed no fractures, and that the soreness would eventually go away. That was a relief. But then he expressed his concern about my tachycardia and syncope, which are fancy doctor words for elevated heart rate and fainting. The EKG had detected a murmur, and he wanted to run a few more tests. I'd be admitted to the hospital and given a stress test and echocardiogram in the morning.

This was not the type of news I was expecting to receive, considering I had come in to make sure I didn't have a concussion. My mom and I sat there for a long time waiting for me to be taken upstairs to a room, and texted people that we thought might like to know what was going on. My wife was grateful for the update, but worried nonetheless; she quickly alerted her dad (who is also our pastor) and got me on our church's email prayer chain. I didn't really want that, but I knew it would likely make her feel a bit better.

I'm not a big fan of the prayer chain for two reasons: First, I rarely pray for who is requesting prayers, which makes me feel guilty; and second, it often reads more like a gossip bulletin than something to approach The Lord about. That probably says more about me than the prayer chain.

All the urgency and swift action I experienced upon my arrival had ostensibly dissipated, because my mom and I sat there for a long time. Nurses came in at regular intervals asking “can you tell me your name and birthdate?” Polite banter usually followed, including jokes about how long it was taking to get me a room.

A couple vials of my blood were taken. A woman in a white coat came in to make sure the documentation of the events leading to my trip there was accurate. My pastor visited. Everything is a bit blurry looking back on it now, but I remember worrying about my wife and our new baby.

There was plenty of time for the uncertainty of the situation to take shape in my worst case scenario prone imagination. Was I going to be okay? If I died, would my family be okay? Would I need medication? Surgery? A mortician? Do they make adult size Batman caskets?

To my disappointment, my answer to “have you ever wanted to go to sleep and not wake up?” had changed. I had foolishly convinced myself that I wasn’t afraid to die; that, at times, dying was even preferable to enduring the suffering that life introduces. But when Old Mr. Bones showed up and winked at me with his empty eye socket I changed my tune pretty quick. Death makes cowards of us all.

The good news of two young women from our church going to stay with my wife that night to help with the baby arrived via text and was a great relief. My wife was still dealing with the repercussions of a difficult birth, and our son had an aversion to sleep that required comforting him in shifts. Knowing she wasn't going into that battle alone allowed me to relax a bit.

Eventually, a nurse with arms covered in tattoos came in and said she was taking me up to my room. She maneuvered me and the bed I had been in all afternoon through the ER and into the hall towards an elevator. I felt like a low budget parade float.

The room was nondescript and utilitarian, with one window that overlooked the roof of the lower floors. Mom hung around for a bit, and then went home to her husband and her cats; there wasn't going to be any new information to learn anyway.

My pastor showed up again a little while later, and I wondered if church members that didn't provide him with grandsons got more than one visit a day. They might. He's a very good pastor. We talked about family stuff for a bit; the girls had arrived at my house to help with the baby, and how I was very grateful for that. But then we got to the stuff I didn't really want to talk about.

“You didn't take Communion last Sunday,” he said.

“No. I didn't.”

“You want to talk about it?”

I didn't, really. The headache that had begun to blossom in the ER was now in full bloom and I was tired. I took a deep breath and decided to be as succinct as possible. “I'm mad at Jesus, and I didn't want him any closer to me than he already is. Especially not on my tongue.”

I had just spent a year in seminary, getting the best grades I had ever gotten in my life, only to drop out because of the needs of my growing family. I couldn't manage the load of a full time job, being a husband and father, and a student, all at once. I was pissed off about it, and I was pissed off at Jesus for leading me there. Not only that, but seminary had revealed to me that I was a fraud. A charlatan. The harder I tried to learn, the less I wanted to - the less I cared. I wasn't nearly as familiar with the Scriptures as I should be, I knew nothing of church history, and learning Koine Greek can fuck right the hell off. Clearly, I am not of the right character for such a vocation.

Why did I ever think I could do that?

I didn't say any of that to my pastor, of course. It was late and I didn't really want to get into it, considering the day's developments.

“It's probably a good thing you didn't take it, then,” he said with a grin. He stayed and we chatted for a bit longer, he prayed for me, and he left. It was nice to be alone after a day filled with people.

Contrary to my expectations, I had trouble getting to sleep. I hadn't had a decent night's sleep since the baby was born, and assumed I'd drop off at the first opportunity, but I lay there worrying about my family.

My wife is too young to be a widow.

She shouldn't have to raise our son alone.

A boy needs his father.

Etcetera and so on.

Finally, with the help of a Buffy the Vampire Slayer marathon on a cable channel I'd never heard of, I was able to fall asleep. Sleep that was, unfortunately, regularly interrupted by nurses coming in to check my vitals. It's true what they say: No rest for the wicked.

Breakfast arrived early the next morning and was immediately followed by a wheelchair ride to a CT scan. I was injected with contrast and inserted into a machine that felt like a coffin that slowly rotated around me. This was not exactly a pleasant experience for me as I don't enjoy confined spaces - especially spaces that turn around me.

Prayer had been scarce for me since the baby was born and dropping my seminary classes, with the exception of “please, God, make this baby go to sleep!” Being closed up in that spinning foot locker, however, compelled me to pray.

I employ two styles of prayer: written prayers that I've memorized, such as the Our Father, the Jesus prayer, and parts of psalms that I like; and prayers ex corde, or from the heart. These are prayers about whatever is on my mind, with little to no preparation. If I had chosen to pray ex corde at that moment, it likely would have been something like “Aaaaaugh! Get me outta this stupid thing, God! I can't breathe! I can't breathe!” followed by hyperventilating.

So I went with things I could close my eyes and meditate on as I prayed them: the Apostles Creed, the Our Father, and the Jesus prayer. I tried to keep my breathing as steady as I could and repeated the prayers until the technician's voice came through the little speaker and said I was done. Like a rotisserie chicken.

After getting extracted from the CT scanner, I was once again treated to a wheelchair ride, this time to the Cardiology department. There, a young woman shaved my chest, which was not an experience I had ever predicted having. She was very professional and careful, which I appreciated. Fortunately for me, I’m not one of those shag carpet chested men and the task was over quickly and painlessly. After she left and a lengthier than preferred wait, another young woman with pretty eyes over her mask came in with an echocardiogram machine and dimmed the lights.

There was an illusion of intimacy in that dark and quiet room with a woman standing at my bedside, her hand pressing a sonar wand against my exposed chest. This would have been another excellent opportunity for me to silently pray.

But no. I felt awkward and nervous, and I started babbling questions about how long she had been doing echocardiograms, how much schooling is required to do that, how many of them she does in a day, and so on.

She was professional and polite, answering my questions plainly while keeping her eyes focused on the throbbing, grainy image of my heart on the monitor in front of her. I suppose I'd be annoyed with someone next to me asking asinine questions while I worked too.

That encounter mercifully behind me, I was wheeled to the test I was least looking forward to: the stress test; the one where they put you on a treadmill and try to run you to death. Or at least heart failure. Don't be alarmed - I survived. In fact, I did very well; I ran my fat ass off on that treadmill wearing a hospital gown, my jeans, and my combat boots. No fluttering, no fainting, no chest pains. To be honest, I felt kind of badass. I hadn't run like that in decades.

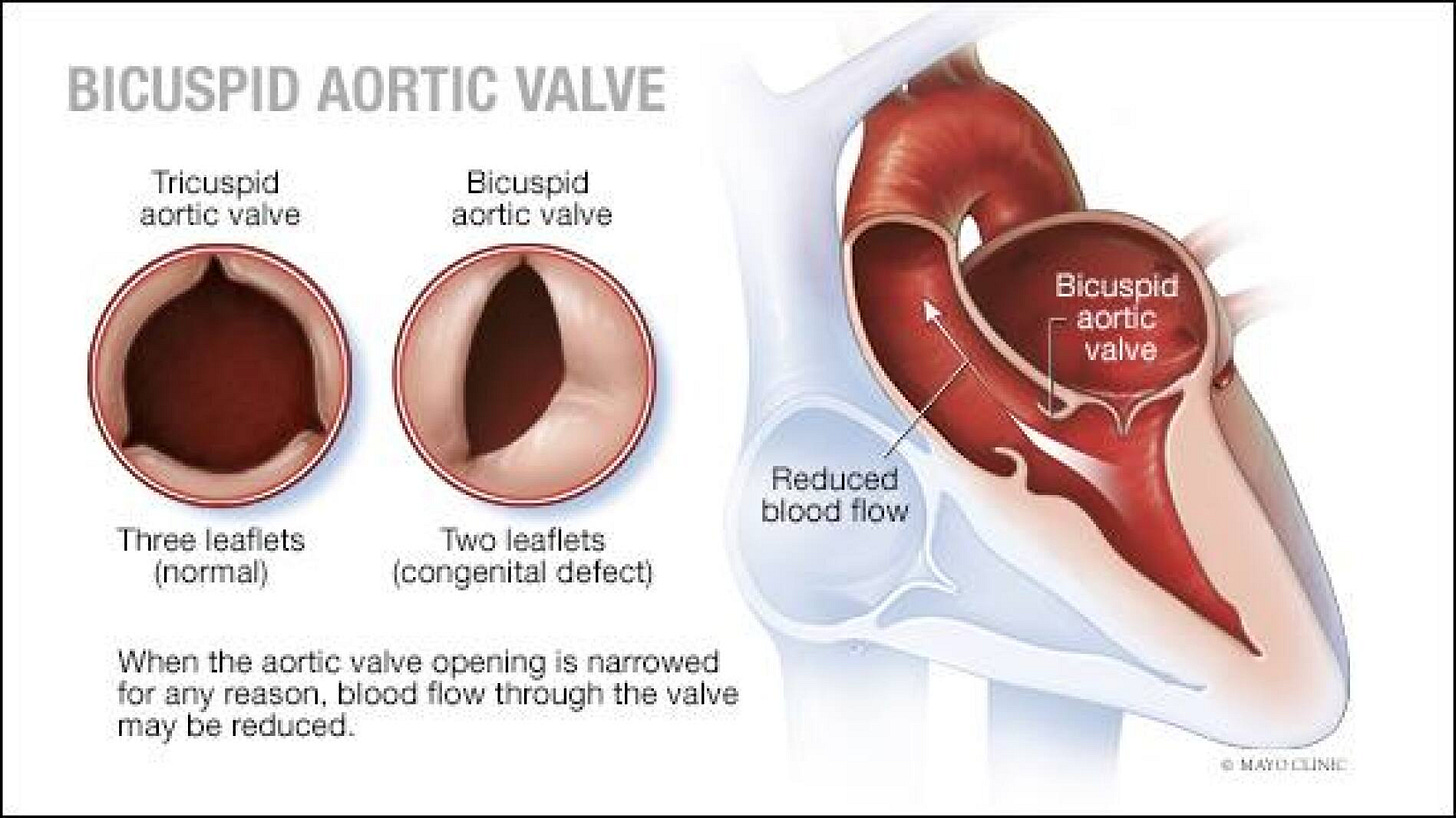

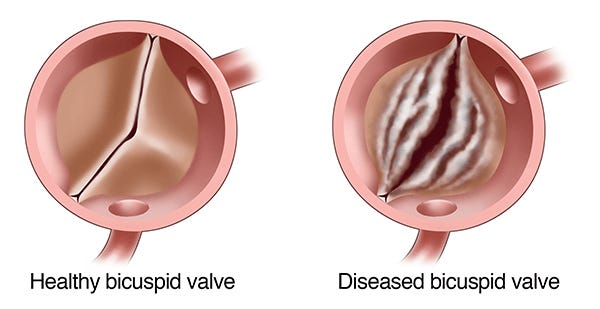

With the tests concluded, the rest of my day was consigned to waiting - for answers, test results, directions… some semblance of what my future was. Very little of that came. What I did get was a diagnosis of Aortic Stenosis and a referral to a cardiologist for a follow up. Fast forward a few months and a transesophageal echocardiogram later, and I can report with some confidence that I have, not only Aortic Stenosis, but a congenital heart defect; I have a bicuspid Aortic valve instead of a tricuspid valve. This might explain why I couldn't run the mile in high school PE… it was either the heart defect or the cigarettes. Let’s say it was the heart defect. I'm on blood pressure medication and I'm supposed to be walking for at least twenty minutes a day to strengthen my heart muscle. I'm hoping that chasing after a toddler, yelling things like “get that out of your mouth!” is a sufficient substitute.

Jeremiah 17:9 kept cycling through my thoughts during all this: “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick; who can understand it?” Obviously, Jeremiah isn't talking about Aortic Stenosis and bicuspid valves, but man's fallen condition. I had become so angry with God - so exasperated with thinking I was doing something that would be pleasing to Him, only to have to give up on it - that I was precariously close to walking away from the faith altogether.

The devil would have me believe that the Lord is punishing me for my faithlessness. The old mystic in me would agree. But the Lord isn't punishing my disobedience by afflicting me with calcification in my defective Aortic valve. All the punishment I justly deserve was taken by Christ on the cross. What I'm enduring are the consequences of being a fallen creature in a fallen world, which the Lord mercifully uses to draw me closer to Himself. I can pray alongside King David:

Create in me a clean heart, O God,

and renew a right spirit within me.

Cast me not away from your presence,

and take not your Holy Spirit from me.

Restore to me the joy of your salvation,

and uphold me with a willing spirit. [Amen!] - Psalm 51:10-12

And when I pray David's words, they become my words - I'm praying ex corde. What a gift it is to have the Holy Spirit reorient our desires! What a mercy it is that God gives us the faith, hope, and love that He demands from us!

I will likely need valve replacement surgery sometime in the not too distant future, but today I have a new heart given to me by the Great Physician (Luke 5:31). When that heart grows weak - as it invariably does - I pray with the father of the spirit possessed boy in Mark 9: “I believe! Help my unbelief!” And He does.

I really resonate with the vulnerable internal narrations, Tait, and was (truly) blessed by the phrase “learning Koine Greek can fuck right the hell off. Clearly, I am not of the right character for such a vocation.” I’ve been (am?) in similar spaces. Crying kids. Confusion vocational leadings. Faith that’s more complex than I want.

////Unrequested feedback/Maybe I’m just struggling aloud: I struggled with the conclusion of this piece. I think its content sounded theologically accurate, but disconnected from the rest of the story or mood. It was a sharp change. Does it feel differently to you? I’d be curious to hear how you arrived at that conclusion—like…I can imagine another essay length addition, which I’d read:)

John, thank you for your comment. I'm grateful for your time and thoughts. I really like the idea of "quiet awareness." I agree that it's different than fear, but it implies a healthy respect for the inevitable, too. My grandfather died of a heart attack at 48. My dad was convinced he would too - but he's 80 and still kicking. It was surreal to find out I have a heart condition at 50 knowing how my grandfather died, so I understand what your saying. Not exactly, but close. Mortality is heavy stuff.

Thank you so much for reading and subscribing. I look forward to checking out your work, too.

Peace,

T.